Net Promoter Score® (NPS®) surveys are often used after customer support transactions. But the question is contextually confusing and the practice yields biased results. NPS® may work fine as a relationship-tracking metric, but when it comes to how the brain evaluates short-term episodes, it’s better to use a different type of survey.

Net Promoter Score® (NPS®) surveys are often used after customer support transactions. But the question is contextually confusing and the practice yields biased results. NPS® may work fine as a relationship-tracking metric, but when it comes to how the brain evaluates short-term episodes, it’s better to use a different type of survey.

Companies often send NPS® surveys to customers after they contact technical support. Triggered by ticket closure, surveys ask, “How likely are you to recommend our company to a friend or colleague?” on a scale of 0 to 10. Customers scoring 9 or 10 are labeled “promoters,” those rating 7 or 8 “passives,” and the remaining 0-6 “detractors.” NPS® is then calculated as the quantity of promoters minus the number of detractors divided by the total number of responses. This approach is very popular. The simple, one-question survey collects customer feedback, and for companies just getting started in customer satisfaction measurement, NPS® can lead to improvements.

Logically, however, business customers don’t buy a product because of the quality of the vendor’s customer support. If fact, good service is generally assumed, and unless the vendor’s support function is award-winning, salespeople tend not to mention it. In practice, B2B customers are more likely to give recommendations considering the product’s value and the entirety of the relationship. So the question about endorsing after a single service experience is out of context.

Human nature also complicates matters. The brain isn’t wired to make a global appraisal accurately after a recent event. Instead, it substitutes the memory of the event itself as a proxy, meaning NPS® winds up measuring the wrong thing.

Memory and decision bias

People experience every moment of life, but we recall only a small fraction of it. Research shows our storytelling minds edit our continuous experiences into discrete episodes, triggered by changes in context.[1] Like a scene fading to black in a movie, the brain uses cues to define event boundaries, establishing the story’s beginning and end. If the event has high relevance, salience and emotional content, the mind strongly “marks” the memory.[2] When we sleep, the brain then consolidates memories from the previous day, discarding all but the most important episodes.

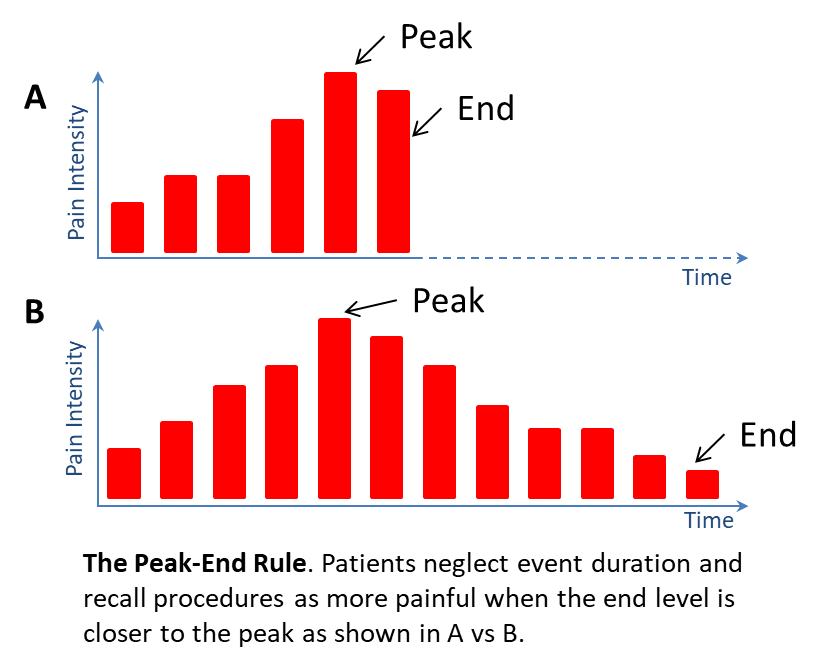

Scientists have found people then recall only bits of these stored events. When patients are asked to revisit a medical procedure, for example, they tend to recollect the peak moment of discomfort as well as the level of pain at the end.[3] Remarkably, patients forget the episode’s duration. They actually prefer a longer period with tapering off pain to a shorter period with high levels of pain at the conclusion. This peak-end rule for episodic recall has been replicated across multiple domains for both good and bad experiences when events were homogeneous, clearly bounded, continuous, completed, and when test subjects played the role of passive participants.[4]

Given the nature of customer service encounters, the peak-end rule applies. Customers often contact Support while highly agitated. Frustrated after encountering a problem, unable to solve it or find helpful information and further delayed by waiting in the queue, people are primed for conflict as the episode begins. A capable Customer Support Representative (CSR) who aligns and empathizes with them, diffuses their anger, and solves the problem in a satisfactory way ensures the negative peak happens only at the beginning and a happy resolution occurs at the end. But if a less attentive CSR ignores the customer’s emotional state (prompting even more anger) and fails to deliver a satisfactory outcome, the customer recalls a very negative Moment of Truth.

Given the nature of customer service encounters, the peak-end rule applies. Customers often contact Support while highly agitated. Frustrated after encountering a problem, unable to solve it or find helpful information and further delayed by waiting in the queue, people are primed for conflict as the episode begins. A capable Customer Support Representative (CSR) who aligns and empathizes with them, diffuses their anger, and solves the problem in a satisfactory way ensures the negative peak happens only at the beginning and a happy resolution occurs at the end. But if a less attentive CSR ignores the customer’s emotional state (prompting even more anger) and fails to deliver a satisfactory outcome, the customer recalls a very negative Moment of Truth.

Following up the support case with the NPS® question then prompts the customer to make a retrospective evaluation and predict a future action. But experiments have shown that when people are pressed for predictions, they use shortcuts. People frequently substitute an evaluation of the evidence at hand without noticing the question they answer is not the same one they were asked.[5] Why? To save time and energy, humans automatically rely on subconscious, emotional heuristics instead of conscious, rational judgment. And when people get stressed or distracted, the phenomenon intensifies. Customers are therefore much more likely to cite satisfaction with their preceding service transaction when asked to evaluate the whole business relationship.

When to use NPS® and when not to

The NPS® question is meaningful in the right context. Neuroscience has shown that when people carefully reflect on multi-episode events, they reconstruct their memories from the fragments, relying on average, not peak or end ratings of each individual experience.[6] Semantic memory also kicks in, fully engaging both fact-based reasoning and emotional processing to give a more accurate assessment. That’s why most experts say NPS® is best used periodically, independent of specific events. It’s suitable as a standalone tracking measure or as part of a more comprehensive, relationship-oriented satisfaction survey.

The NPS® question is meaningful in the right context. Neuroscience has shown that when people carefully reflect on multi-episode events, they reconstruct their memories from the fragments, relying on average, not peak or end ratings of each individual experience.[6] Semantic memory also kicks in, fully engaging both fact-based reasoning and emotional processing to give a more accurate assessment. That’s why most experts say NPS® is best used periodically, independent of specific events. It’s suitable as a standalone tracking measure or as part of a more comprehensive, relationship-oriented satisfaction survey.

When it comes to measuring customer service interactions, leaders should set aside NPS® and use more traditional customer satisfaction surveys. Questionnaires should be brief, asking only about the factors which truly impact the quality of the interaction. These factors may include how well the agent listened and understood the problem, reflected their concerns, and resolved the issue. More relevant, actionable and targeted information can then be used for process improvement, CSR training and coaching.

NPS® is a popular tool and one that belongs in the mix, but it’s not appropriate for every situation. Leaders should follow good brain science and choose the right tool for the job.

Net Promoter, Net Promoter System, Net Promoter Score, NPS and the NPS-related emoticons are registered trademarks of Bain & Company, Inc., Fred Reichheld and Satmetrix Systems, Inc.

Sources:

[1] Sols, I., DuBrow, S., Davachi, L., Fuentemilla, L. (2017) Event boundaries trigger rapid memory reinstatement of the prior events to promote their representation in long-term memory. Current Biology, 2017; 27 (22): 3499

[2] Damasio, A. (1996). The somatic marker hypothesis and the possible functions of the prefrontal cortex. Phils. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci, 351, 1413-1420

[3] Varey, C., Kahneman, D. (1992) Experiences extended across time: Evaluation of moments and episodes. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 5, 169-186

[4] Fredrickson, B., (2000). Extracting meaning from past affective experiences: The importance of peaks, ends, and specific emotions. Cognition and Emotion, 2000, 14 (4) 577-606.

[5] Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, Fast and Slow. Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, New York, pp. 188.

[6] Geng, X., Chen, Z., Lam, W., and Zheng, Q. Hedonic evaluation over short and long retention intervals: The mechanism of the peak–end rule. Behavioral Decision Making 26: 3, July 2013, pp 225-236.