Don’t play the blame game

It’s easy to point the finger at salespeople, but when it comes to improperly set expectations, customers themselves are sometimes to blame. CSMs should resist jumping to conclusions and leaders should implement safeguards.

It’s easy to point the finger at salespeople, but when it comes to improperly set expectations, customers themselves are sometimes to blame. CSMs should resist jumping to conclusions and leaders should implement safeguards.

Criticizing salespeople for over-selling is certainly justifiable. Driven by quota pressure or their own greed, salespeople can sometimes qualify opportunities poorly or make wild promises in order to close a deal. Customer Success professionals are then left to clean up the mess. They must work especially hard to regain trust, overcoming a disastrous first impression that the customer’s been lied to. It’s frustrating for everyone.

Regardless of what salespeople do, however, buyers are sometimes the ones at fault when their own beliefs don’t match reality. How does this happen? They’re human. It turns out they suffer the same systematic judgment errors we all do.

Caveat emptor

Under U.S. law, buyers are afforded certain legal rights when dealing with vendors. In the case of problems, the courts say customers can return or reject products, or require that any defects in workmanship be remedied or cured at the vendor’s expense.

Few software companies, however, go beyond these basic buyer protections. In fact, many specifically add disclaimers to limit their liability for merchantability (meeting marketing claims), fitness for a particular purpose, or any damages that could arise from the purchase or use of software. This means it’s up to the customer to make an informed buying decision.

The law expects customers to make logical, rational choices. The problem, of course, is that we humans tend to do just the opposite.

Systematic errors

Neuroscientists say humans are always of two minds, the rational and the emotional. System 1 is our ancient, intuitive, reflexive self which operates according to simple rules. System 2 is our relatively new, logical, reflective self which deals well with ambiguity and nuance. We are most familiar with the internal dialogue of our System 2, but System 1 is always on and running in the background, swaying every choice we make. In fact, mounting evidence suggests that all decisions are made by System 1. Our subconscious simply fools us into believing otherwise.

System 1 is incredibly fast and powerful, but it can be heavily biased, causing us to make irrational judgments. For instance, scientists have shown that language alone can alter people’s behaviors. In one experiment, 93% of PhD students registered early when a penalty for late registration was emphasized, but only 67% did when it was presented as a discount. Framing effects is just one example. We are blissfully unaware that our subconscious routinely places a heavy hand on our decision making scale.

Nobel Laureates Daniel Kahneman, Amos Tversky, and Richard Thaler studied irrational side of human decisions, creating the new field of behavioral economics. They identified a number of heuristics, or decision rules, System 1 relies upon to make quick judgments. These rules distort logic, causing people to jump to the wrong conclusions. Critical thinking is entirely absent with System 1, and if System 2 fails to check assumptions, decisions made on impulse will stand. When people feel stressed or depleted, as is often the case in modern business, these effects magnify.

That’s what you heard, but that’s not what we meant

The customer’s human nature can lead to dangerously mis-set expectations. Absent direct experience, the mind fills in the blanks. The heuristics customers automatically rely on can cause significant headaches for people working downstream after the sale, such as:

- Causal errors. System 1 responds strongly to coherent stories and presumes cause-and-effect when it’s not warranted. Prospects may, for example, read a success story about a customer in a similar industry and simply assume the product also fixes their particular problem without questioning the validity of the assumption.

- Anchoring effects. People inappropriately weight the first tidbit of information (often a number) more heavily than data that follows. For example, a sales prospect may hear “amazing 40% improvement in the first thirty days” and use it as their starting benchmark instead of basing it upon the typical, average results.

- Confirmation bias. People tend to notice information that supports their beliefs and ignore information that contradicts them. Once System 1 sets an expectation or anchor, customers will stubbornly adhere to it, such as dismissing more conservative outcome estimates raised by others.

- Planning fallacy. Humans regularly underestimate the time, cost and effort required to complete tasks. We’re naturally programmed to be optimistic, perhaps because it encourages persistence in the face of obstacles. Even without a salesperson’s glowing predictions, customers are likely to favor the best-case timeline for deployment rather than the realistic one.

How can companies ensure customers preserve reasonable expectations throughout the sales process, regardless of who sets them? Prompting customers to think analytically at certain times triggers their System 2 processes, suppressing System 1’s propensity for exaggeration.

How can companies ensure customers preserve reasonable expectations throughout the sales process, regardless of who sets them? Prompting customers to think analytically at certain times triggers their System 2 processes, suppressing System 1’s propensity for exaggeration.

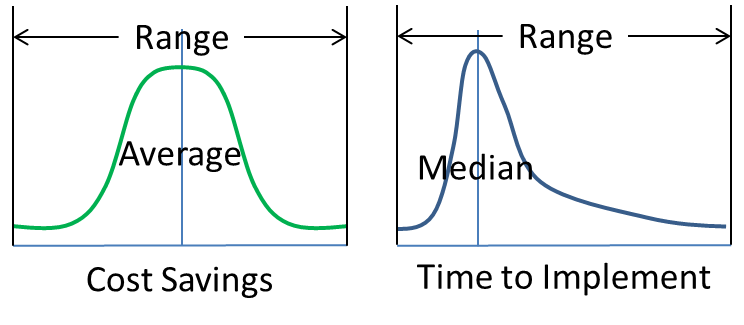

It’s easy to activate critical thinking and keep customers grounded. Salespeople can be trained to go beyond a basic demo and ask the customer to verify that the product meets their specific needs. Company leaders can insert a standard slide in the sales deck that shows the average and distribution of customer outcomes, encouraging thoughtful discussions about how to maximize results. Closing rates won’t be affected, and it’s still OK to highlight the eye-popping, exceptional cases, provided sellers acknowledge them for what they are. If the firm clearly and carefully separates what’s expected from what’s possible, prospects can still get excited about the upside while maintaining an appreciation for what’s likely.

CSMs, just like the customers they serve, should avoid jumping to conclusions: salespeople are not always at fault when customers believe unrealistic outcomes. And when companies understand how cognitive biases work and prevent customers from suffering the consequences of their own human nature, new business relationships can reliably get off on the right foot.