Most SaaS executives assume customer churn rises the minute a company loses its competitive edge. Not so. If customers are switching to top rivals in appreciable numbers, executives should be especially nervous—the situation is already much graver than they think. Research suggests customers leave because they’re long dissatisfied and now view the competition is twice as good. Executives must heed the warnings and overcome their own biases if they want to turn things around.

Thinking that doesn’t add up

Strangely, people tend to avoid loss even when they are faced with the possibility of larger gains. Research shows that people require more compensation to give up a possession than they would have been willing to pay to obtain it in the first place.1 Even when all things are equal, repeated experiments show people subjectively weigh gains much differently than losses.

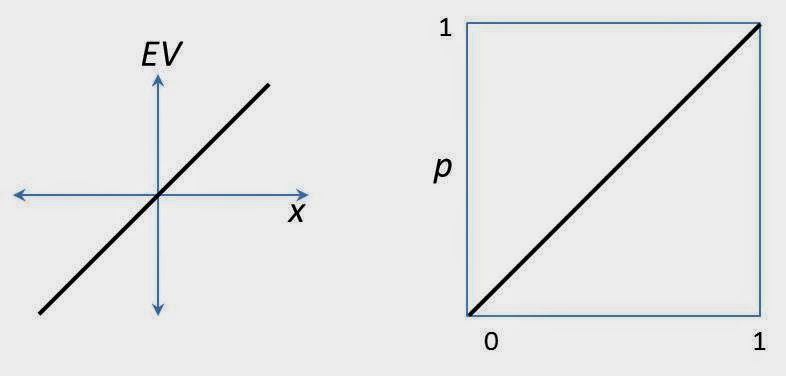

In 1654, French mathematicians Blaise Pascal and Pierre de Fermat proved that the expected value (EV) of an investment depends on the amount (x) and the probability of its outcome (p):

EV = px

For example, say a coin flip determines you collect $100 for heads and $0 for tails. Since the probability of obtaining heads using a fairly balanced coin over a large number of trials is 50%, the likely payout, on average, is $100 * 50% = $50. As shown by the charts, this relationship is true no matter the amount or the probability used in the calculation. Today many financial decisions are made using Pascal and Fermat’s expected value.

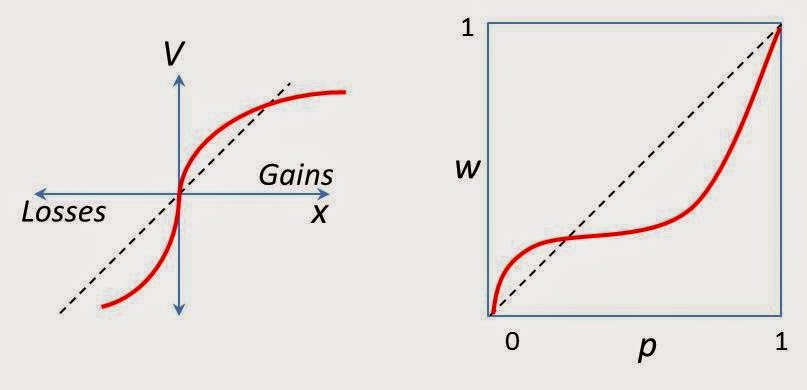

But that’s not how most people make decisions. Faced with a choice of receiving $3,000 for sure or taking an 80% chance to win $4,000, most people will keep the money, even though the expected value for taking the risk is greater ($4,000 * 80% = $3,200). Prospect Theory in modern economics asserts that rather than apply logic, people instinctively determine value (V) by weighting differences in probabilities (p) and amounts (x) shown below:

V(x,p) = w(p)v(x)

The clean, linear function reflecting objective reality is suddenly replaced with this subjective, nonlinear aberration:2

Intuitively, the irregular curves hold water. People would rather take a 95% chance losing $100 than pay $85 for sure because amounts “feel” equally painful and 95% probability “feels” less than certain. On the other hand, people will take a 5% chance to win $100 instead of choosing $13 cash because $100 seems a lot more than $13, and 5% seems like a realistic chance.

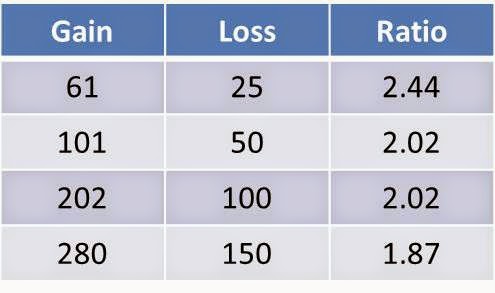

Scientists also discovered that when they tested 50-50 win-loss scenarios, subjects said the following ratios equally attractive to when compared with receiving nothing:3

In other words, faced with even odds, most people want 2:1 upside before taking a risk. A bird in the hand is indeed worth two in the bush!

Why do we think this way? Most scientists believe it’s a vestige of our human evolution. In prehistoric times, survival probably depended upon playing it safe when we had resources and taking risks when we had none. In the modern age, however, our success depends on scientific and social advances, situations requiring thoughtful reflection instead of impulsive action. But since our complex reasoning evolved relatively recently, it often takes a back seat to our more primitive instincts, even when the consequences aren’t life or death. Despite today’s advances, subconscious emotion, not conscious logic, often rules the day. This explains why regardless of the odds, we continue to buy lottery tickets.

Tip of the iceberg

Evidence shows people are far more likely to stay in a bad situation than pursue a better one. What this means for SaaS companies is that once customers subscribe, they are likely to stay. But when customers switch, it’s very serious. Their actions show they’ve already had enough and customers realize competitors offer significantly greater advantages.

As humans themselves, executives likewise have a choice. They can either look logically at their company’s performance gaps and do something about them, or scoff at their customers’ subjectivity and do nothing at all. Like their customers, executives must overcome their own, natural inclination to preserve the status quo even when things are going south. If they can see the advantages of change and take risks to improve organizational performance faster than their customers get fed up and go elsewhere, churn reduction has a fighting chance. Otherwise, perhaps, companies with more evolved thinking will be the survivors.

Did you enjoy this article? Subscribe to Excel-lens now and never miss another post?

- Kahneman, D., Knetch, J. L., and Thaler, R. H. (1990). Experimental tests of the endowment effect and the Coese theorem. Journal of Political Economics, 98, 1325-1348.

- Kahneman, D., and Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: an analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 4, 263-291

- Tversky A., and Kahneman, D. (1992). Advances in prospect theory—cumulative representation of uncertainty. Journal of Risk Uncertainty, 5, 297-323