Build a better organizational habit this year

After annual planning, most organizations lose momentum and progress soon grinds to a halt. What can be done to alter the status quo and ensure this year’s plans actually get carried out? Perhaps it’s time to look at how to promote a habit of execution.

A chronic problem

Organizations struggle with execution, the challenge caused mostly by internal factors. Various experts estimate 70% of company initiatives fail,[1] and according to a study by McKinsey, 72% of the time it’s due to managers and employees resisting change.[2] Inability to overcome internal hurdles even impacts careers in the corner office. CEO dismissals have historically run 16%-30%[3] because of a lack of execution, not a lack of strategy.[4]

Experts cite a number of factors. Many say ineffective change management is to blame. Others say it’s a lack of emotional intelligence on the part of many CEOs. Still others point to a lack of accountability, inappropriate metrics or counterproductive bonus structures.

All of these may be drivers, but an organization’s lack of self-control may ultimately be responsible. Authors Larry Bossidy and Ram Charan say execution is a discipline that must be integrated into a company’s strategy, goals and culture, and personally reinforced by the senior leader.[5] Companies excelling in an enterprise-wide approach reap high returns. According to author Jim Collins, organizations exhibiting fanatic discipline, defined as extreme consistency of action, goals, performance standards and methods, tend to outperform rivals by a factor of ten.[6]

While many experts describe the desired performance, few explain how the organizational behavior itself can be acquired. A closer look at neuroscience suggests new perspectives.

Start with neurons

Our miraculous brains are the pinnacle of human evolution. Most scientists think that despite our millions of years of natural selection, we humans became fully capable of conscious thought only recently, around 100,000 years ago, a relative blink in geologic time.

Because of its nascent development, our consciousness makes up only about five percent of our total neural activity. Bombarded by modern-day stimuli, our mental processing suffers intense demand coupled with limited computing resources. To manage the high cognitive load, our brain uses a variety of shortcuts, such as offloading simpler tasks to our brutish, but lightning-fast subconscious.

It’s the process of habituation. Our midbrain’s basal ganglia rewire repetitive tasks so our minds can perform them instinctively. What once required thoughtful contemplation eventually occurs automatically, below our conscious awareness. For example, the first day we drive to work we must pay close attention to all the turns, but after a month or so, we arrive unable to recall the commute’s specific details.

But the brain makes tradeoffs with this processing arrangement. While our conscious mind learns quickly and deals with complicated matters easily, our subconscious learns slowly and must operate according to simple rules. And once trained, our reflexive system resists change. A habit becomes very hard to break.

The habit loop

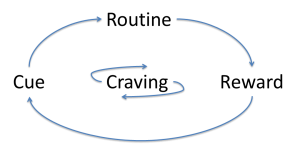

Author Charles Duhigg describes a simple behavioral model for understanding how habits work.[7] A sensory cue triggers the subconscious to enact a routine, which in turn leads to a reward. The reward itself is biochemical. Our brain releases dopamine, a neurotransmitter that causes animals like us to repeat beneficial behaviors. We crave this substance, whether it’s produced in response to basic physical or complex social actions.

Duhigg points out that most companies focus exclusively on individual rewards and recognition as a way to influence behaviors. But as the model shows, carrots and sticks only go so far. The desired routine must be simple, clear and repeatable. A sensory indicator must trigger the cycle. The behavior must satisfy a primal need. And the process requires many recurrences to become established. Scientists say the average time to acquire a habit is 66 days with a range of 18–254 days, depending on the behavior and its frequency.[8] Leaders must consider all aspects of this loop if the goal is to improve performance by modifying worker habits.

Duhigg points out that most companies focus exclusively on individual rewards and recognition as a way to influence behaviors. But as the model shows, carrots and sticks only go so far. The desired routine must be simple, clear and repeatable. A sensory indicator must trigger the cycle. The behavior must satisfy a primal need. And the process requires many recurrences to become established. Scientists say the average time to acquire a habit is 66 days with a range of 18–254 days, depending on the behavior and its frequency.[8] Leaders must consider all aspects of this loop if the goal is to improve performance by modifying worker habits.

Solutions that leverage our natural tendencies

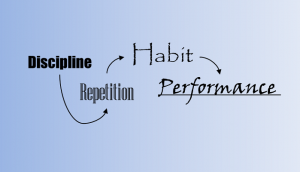

As Charan, Bossidy and Collins point out, discipline improves performance, and formal processes and structures can help. Discipline begets repetition, repetition begets habits, and habits beget performance. For example, to overcome the annual  planning “shelfware” syndrome, leaders should adopt a planning and review calendar discipline. Executives can create a schedule including triggered date reminders (cues) and routine agendas to review progress, align activities between levels and teams (routines), and give feedback (rewards). In time, the new corporate ritual will satisfy deep, collective needs for security and growth and foster a habit of execution across the enterprise.

planning “shelfware” syndrome, leaders should adopt a planning and review calendar discipline. Executives can create a schedule including triggered date reminders (cues) and routine agendas to review progress, align activities between levels and teams (routines), and give feedback (rewards). In time, the new corporate ritual will satisfy deep, collective needs for security and growth and foster a habit of execution across the enterprise.

People must also change their own habits. Rather than let the urgencies of the day subvert their efforts to become more proactive, leaders must impose better self-discipline. Author Stephen Covey says it best, “The key is not to prioritize what’s on your schedule, but to schedule your priorities.”[9] I strongly recommend my clients calendar two-hour, recurring meetings every week dedicated exclusively to making progress on plans and improvement projects. The visual cue triggers them to set aside time to chip away relentlessly at meeting their goals, week after week. Achievement is the reward and all the benefits that come with it.

Resolve to make 2016 different. This year, adopt the habit of execution.

Sources:

[1] Hammer, M. and Champy, J. (1993) Reengineering the corporation: a manifesto for business revolution, London: Nicholas Brearly; Beer, M. and Nohria, N. (2000) Cracking the code of change. Harvard Business Review, Vol.78, Issue.3, pp.133-141; Kotter, J.P. (2008) A sense of urgency. Boston: Harvard Business School Press; Senturia, T., Flees, L. and Maceda, M. (2008) Leading change management requires sticking to the plot. Bain and Company. Accessed at http://www.bain.com; Hughes, M. (2010) Managing Change: A Critical Perspective. Wimbledon: CIPD Publishing.

[2] Kitching, E., and Shaibal, R (2013) 70% of transformation efforts fail—make your program succeed with proven strategies to generate momentum and sustain long-term change. Wave/McKinsey Solutions. Accessed at: http://www.slideshare.net/aipmm/70-26633757.

[3] Tonello, M. (2015) New statistics and cases of CEO succession in the S&P 500. Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance and Financial Regulation. Accessed at: http://corpgov.law.harvard.edu/2015/04/23/new-statistics-and-cases-of-ceo-succession-in-the-sp-500/

[4] Charan, R., and Colvin, G. (1999) Why CEOs fail. Fortune Magazine, June 21, 1999.

[5] Bossidy, L. and Charan, R. (2002) Execution: the Art of Getting Things Done. Crown Business, ISBN 0609610570.

[6] Collins, J. and Hansen, M. T. (2011) Great by Choice: Uncertainty, Chaos and Luck—Why Some Thrive Despite Them All. HarperBusiness; 1 edition, ISBN 0062120999

[7] Duhigg, C. (2014) The Power of Habit: Why We Do What We Do in Life and Business. Random House Trade Paperbacks. ISBN 081298160X.

[8] Lally, P., van Jaarsveld, C. H. M., Potts, H. W. W., & Wardle, J. (2010). How are habits formed: Modelling habit formation in the real world. European Journal of Social Psychology. October 2010.

[9] Covey, S. (1989) The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People: Powerful Lessons in Personal Change. Free Press; Revised edition (November 9, 2004). ISBN 0743269519.